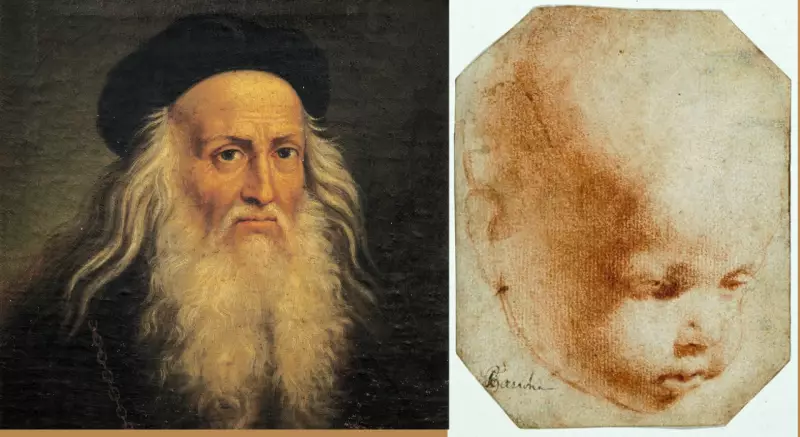

In a remarkable fusion of art history and cutting-edge science, researchers have successfully recovered minuscule traces of DNA from artefacts associated with the legendary Renaissance polymath, Leonardo da Vinci. This pioneering work opens a new, unexpected scientific window into the life of one of history's most studied figures, whose genius spanned painting, anatomy, and engineering.

The Hunt for Biological Signatures

The international team of scientists employed a novel, minimally invasive swabbing technique, akin to COVID-19 test swabs, to collect biological material from precious historical objects. This approach is part of a growing scientific field known as arteomics, which analyses biological traces left on artefacts to understand their history, handling, and environment. The study's preprint was published on bioRxiv, indicating it awaits formal peer-review.

The artefacts tested include a red chalk drawing on paper known as 'Holy Child', possibly created by da Vinci, and letters written by his family members, including his grandfather's cousin, Frosino di Ser Giovanni da Vinci, held in an Italian archive. In April 2024, microbial geneticist Norberto Gonzalez-Juarbe carefully swabbed the 'Holy Child' drawing from a private New York collection.

Genetic Clues and Tuscan Roots

The analysis yielded a mix of human and non-human DNA. Intriguingly, some Y-chromosome DNA sequences found on the 'Holy Child' and a cousin's letter appear to belong to a genetic grouping linked to shared ancestry in Tuscany, Italy, where Leonardo was born in 1452. When compared to large genetic databases, the closest match fell within the broad E1b1/E1b1b lineage, common in southern Europe, North Africa, and the Near East today.

"We recovered heterogeneous mixtures of non-human DNA," the researchers noted, "and, in a subset of samples, sparse male-specific human DNA signals." To minimise contamination risk during this search for male-line DNA, the collection was carried out exclusively by female scientists.

Environmental Fingerprints and Historical Context

The non-human DNA provided a rich tapestry of environmental clues. Researchers found DNA from sweet orange trees cultivated in Medici gardens during the Renaissance, a detail that may point to the artwork's historical context and potential authenticity. Other plant traces, like Italian ryegrass and willow (Salix), help situate the artefacts geographically and culturally in 15th-16th century Italy, where willow was used in artisan workshops.

"The unique presence of Citrus spp in the 'Holy Child' may provide a direct link to historical context," the scientists stated, while cautioning that plant DNA can come from various sources like dust or later handling.

Why definitive proof remains elusive is a major challenge. As anthropologist David Caramelli of the University of Florence explained to Science magazine, establishing unequivocal identity is "extremely complex." There are no known direct descendants of da Vinci to provide a definitive genetic match, and his burial site was disturbed centuries ago, scattering his remains.

The study also included control samples: letters, drawings by other artists like Filippino Lippi, frames, and modern cheek swabs. The researchers caution that while the Y-chromosome markers are compatible with patterns from Leonardo-associated objects, the DNA is a mixture from centuries of handlers. Future work is needed to better distinguish historical signals from modern contamination. This groundbreaking research nonetheless marks a significant step in using genetic archaeology to touch the intangible legacy of a master.