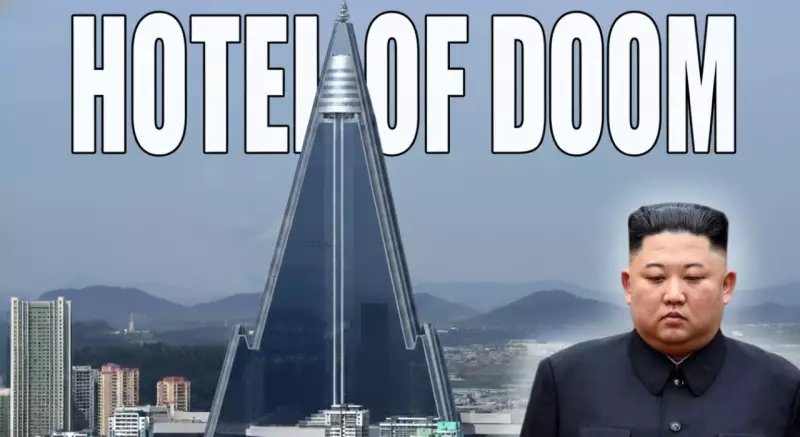

In the heart of Pyongyang, a colossal glass pyramid dominates the skyline, appearing from most angles as a finished, futuristic marvel. This is the Ryugyong Hotel, North Korea's tallest building, standing at 330 metres with a rumoured 105 storeys. Designed to be a luxury complex with over 3,000 rooms and five restaurants, it has earned grim nicknames like the 'Hotel of Doom' and the 'Phantom Hotel'. Despite its polished exterior, not a single guest has ever stayed there. Behind its gleaming facade lies a story of ambition, stagnation, and raw concrete.

The Man Who Unlocked the Phantom Hotel

Very few outsiders have ever seen the interior of this enigmatic structure. One of the rare exceptions is Simon Cockerell, the Managing Director of Koryo Tours, a Beijing-based travel company specialising in trips to North Korea since the 1990s. Cockerell didn't plan this career; it found him through an amateur football league in Beijing, where he met the founders of Koryo Tours and a North Korean businessman. Taking a job with them, he has since visited the country more than any other Westerner, building connections over two decades that eventually granted him access to the Ryugyong's hollow core.

A Dream Deferred: The Hotel's Stalled History

North Korea began constructing this ambitious hotel in 1987. It was conceived as a symbol of prosperity, meant to rival a supertall hotel being built in Singapore. The design was bold: a 330-metre pointed tower with three wings, each 100 metres long, narrowing into a cone at the top. Construction pushed ahead until the early 1990s, then halted abruptly for 16 years when funds and materials ran dry. As the world witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of the internet, the bare concrete frame of the Ryugyong stood frozen over Pyongyang.

Work restarted in 2008, focusing on applying the iconic glass cladding. Forecasts promised a completed exterior by 2010 and interior by 2012, with speculation about an international hotel group taking over. None of it materialised. The exterior reached its current, polished state, but the interior was never finished.

Cockerell's Rare Glimpse Inside

During the renewed construction phase, Cockerell's long-standing access allowed him a unique visit. He and a colleague approached the hotel as workers were removing the final glass panels from a crane at the summit using a helicopter. What he entered was not a luxury lobby but a vast, empty concrete shell. His photographs reveal a grand central space with barriers along unfinished floor edges, empty lift shafts, and no visible rooms. It was an impressive yet eerie monument to a project that exists only in outline.

Cockerell has not been back inside since. From the street, a lit lobby floor is sometimes visible behind the glass, but whether it's a finished level or a facade is unknown. The state rarely allows anyone close enough to verify.

Engineering a Concrete Giant in a Windy World

The Ryugyong is an engineering anomaly. Most supertall towers use steel frames to flex with wind. This one is built almost entirely from concrete, which is strong but not tensile. To stabilise a concrete structure of this height, engineers gave it a massive footprint, with three wings acting as stabilisers that taper towards the top. This pyramid shape isn't just for show; it's a crucial design to prevent the 330-metre tower from becoming unstable in strong winds.

Over the years, rumours swirled about unsafe concrete and misaligned lift shafts. Cockerell considers these claims exaggerated. He suggests the hotel's problems are less about unique engineering failure and more about chronic underfunding and shifting state priorities.

A Static Symbol in a Slowly Changing Nation

While the hotel has remained empty, North Korea has undergone subtle changes. Cockerell notes the spread of mobile phones, a small urban middle class in Pyongyang, and more visible personal consumption. However, state controls remain tight, with most citizens cut off from the global internet. After Covid-19, borders were sealed, only tentatively reopening in 2024 for events like the Pyongyang marathon.

Through it all, the Ryugyong Hotel has stood as a constant—lit up on special occasions, but dark and inaccessible. It has never hosted a guest, conference, or known test run. For observers like Cockerell, it is a fixed reference point: a giant, seemingly complete pyramid that reveals its profound emptiness only to the very few who step inside.

What Does the Empty Tower Represent Now?

The world has many unopened skyscrapers, but the Ryugyong is unique. It sits in one of the planet's most closed countries, has been a part of Pyongyang's skyline since the late 1980s, and was designed as a flagship showpiece. Whether it will ever be finished, repurposed, or left as a sealed monument is a decision solely for the North Korean state. For now, it remains exactly as Cockerell found it: an enormous, echoing concrete shell, built at a cost of approximately $800 million for guests who never arrived.