For the third consecutive year, Gurgaon has witnessed a rise in its groundwater levels, offering a glimmer of hope in its long-standing water crisis. The latest pre-monsoon data reveals the city's average water table depth at 30.6 metres, marking the shallowest level in nearly a decade and showing an improvement of three metres from last year.

A Decade of Decline Followed by Recent Rebound

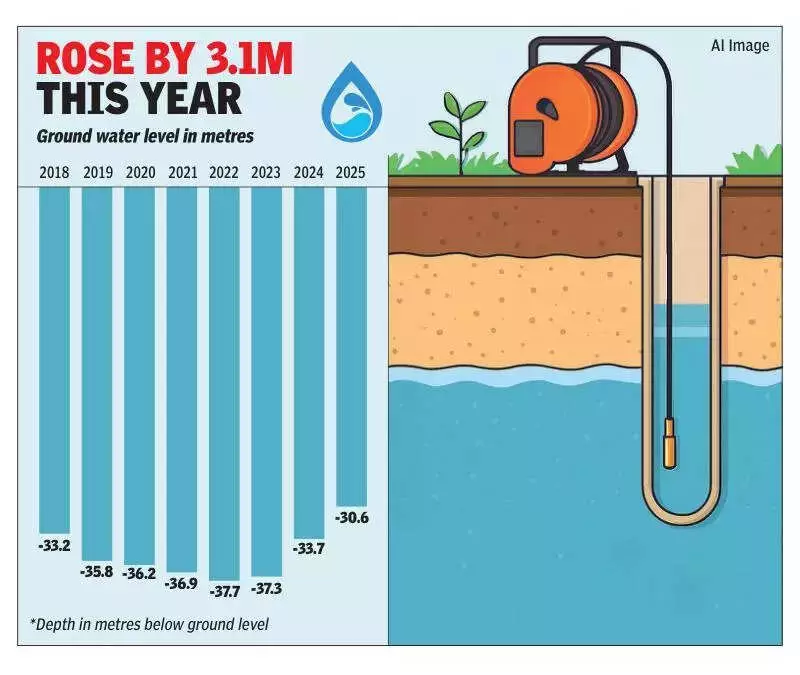

However, a closer examination of the data tells a more complex story. This recovery appears to be more a gift from generous rainfall than a result of transformative changes in the city's water usage or recharge practices. Historical data from the district groundwater cell illustrates a troubling seven-year trend. In 2018, the pre-monsoon water table was at 33.2 metres, followed by a steady and alarming decline: 35.8 metres in 2019, 36.2 metres in 2020, 36.9 metres in 2021, and a deep 37.7 metres in 2022. By that point, officials had acknowledged that Gurgaon was extracting far more water than it could naturally replenish.

The downward spiral showed its first sign of reversal in 2023, with the level improving slightly to 37.3 metres. This was followed by a significant jump to 33.7 metres in June 2024 and the current reading of 30.6 metres in 2025. While officials attribute this positive trend to stricter action against illegal borewells, curbs on groundwater use for construction, and a push for rainwater harvesting, independent experts point to a different primary cause.

Rainfall, Not Reform, Drives Recovery

Experts are unanimous in their assessment that the recent rebound is largely due to unusually high rainfall during the 2024 and 2025 monsoons, rather than systemic improvements. "Gurgaon's water table has indeed rebounded, but this rise largely coincides with the unusually wet monsoons," said Fawzia Tarannum, co-founder and strategic lead at GuruJal. She highlighted the persistent gap between extraction and recharge: "The city continues to extract more than twice its sustainable groundwater limit, withdrawing about 43,262 ham (hectare-metres) in 2024 against a recharge capacity of only 20,333 ham."

This over-extraction is not new. Gurgaon has been officially classified as an 'overexploited' zone since 2013 and remains one of Haryana's biggest consumers of groundwater. A government study from 2024 underscores the severity, showing the city extracted 212% of its permissible annual groundwater limit, placing it third in the state for over-extraction, behind only Kurukshetra and Panipat.

An Uneven Recovery and a Call for Structural Change

The recovery is also uneven across the district. Block-wise data for this year shows stark variations:

- Gurgaon block: 33.8 metres

- Pataudi block: 37.8 metres

- Sohna block: 25.7 metres

- Farrukhnagar block: 22.7 metres

Experts caution that the better performance in areas like Sohna and Farrukhnagar is also linked to heavy rainfall rather than long-term sustainable management.

Professor Gauhar Mahmood from Jamia Millia Islamia's civil engineering department echoed the sentiment, stating, "The credit for improvement of water level should be given to nature," noting the city's minimal efforts in harvesting or utilizing rainwater for recharge.

The reliance on borewells continues because many neighborhoods still lack reliable piped water supply. Experts warn that without decisive action, the current gains will be temporary. "The ongoing efforts by a few NGOs and govt agencies, while important, remain a drop in the ocean," added Tarannum. She called for a combined strategy of enhanced recharge, rigorous regulation, aggressive rainwater harvesting, universal piped supply, and rational water pricing.

VS Lambha, a hydrologist at the Haryana groundwater cell, issued a stark warning: "Groundwater is not an infinite reserve that we can keep mining without consequence. Without strict regulation and local recharge efforts, large parts of the district will soon be pumping air, not water." The message is clear: while the rising numbers are welcome, true water security for Gurgaon will require moving beyond dependence on monsoon bounty to implementing hard, structural reforms in water governance.