The Shah's Symbolism: A Cultural and Historical Lens on Iran's Turmoil

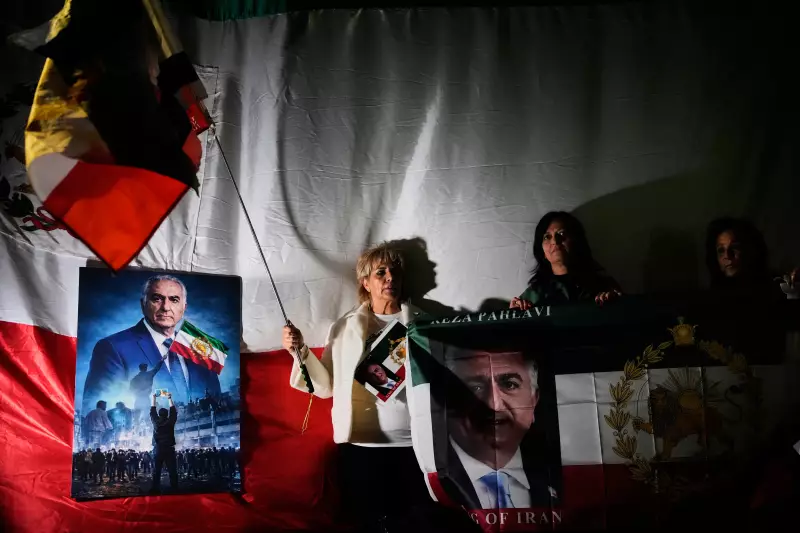

In recent days, images from Berlin show Iranian women holding posters of exiled prince Reza Pahlavi, demanding the "King of Iran" return. This scene highlights a counterintuitive idea: the king as a symbol of resistance. It reflects deep-seated cultural memories and historical narratives in Iran.

Understanding the Support for Pahlavi

First, let's address some caveats. Media coverage might exaggerate Pahlavi's ground support. Many fear he could become a puppet for the US or Israel. His democratic claims remain untested, and memories of his father's authoritarian rule linger. Perhaps protesters use him as a convenient symbol to oppose the regime, especially with no other prominent opposition figure available. Regime change may not happen, and Pahlavi's return to power might seem unrealistic.

Despite this, his presence in the frame is significant. It taps into a legendary notion of a king returning in times of need, similar to Arthurian tales. Historically, support for exiled kings often comes from specific groups, like displaced elites who thrived under former regimes. For instance, French émigrés during the Revolution or Iranian émigrés today, who sometimes call themselves "Persian," fit this pattern.

Photos from the Shah's era, showing women in mini-skirts, depict an urban elite world. This contrasts with the conservative rural populace supporting the current Islamic regime. Protesters chanting "victory to the Shah" likely include this elite and disaffected youth with no direct experience of monarchical rule.

Cultural Memory and the King's Role in Iranian Identity

Beyond Pahlavi, cultural memory plays a key role. The figure of the king has been a powerful motif in Iranian history for millennia, often reinforced by propaganda. Moments of Iranian assertion have aligned with kings emphasizing their Iranian-ness.

This connection dates back to ancient times. In the fifth or sixth century BCE, Darius the Great used propaganda in his Behistun Inscription. He identified as "an Aryan, son of an Aryan, a Persian, son of a Persian" and linked himself to Cyrus the Great. Modern historians suspect Darius might have orchestrated a coup, using propaganda that lasted for centuries.

Later, the Sasanians promoted a Zoroastrian mythic past and their Iranian ruler identity. After the Arab conquest, Iranian kings re-emerged, using pre-Islamic titles and claiming Sasanian lineage. The Shahnameh, or "book of kings," composed centuries later, cemented this cultural legacy.

Over the second millennium, the Persianate world spread from Constantinople to Vijayanagara, exporting a cultural package that included the idea of a justice-dispensing king.

The Pahlavi Dynasty's Propaganda Efforts

The Pahlavis, though only two kings old, skillfully used propaganda. In 1971, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi hosted a grand celebration of "2,500 years of the Empire of Iran" at Persepolis. He issued commemorative coins and adopted the Cyrus Cylinder as a national symbol, calling it the "first charter of human rights." This wove together royal tradition and a modern, liberal image.

Current Factors and Future Implications

Today, several factors converge: the yearning of the old elite, the desperation of youth, the need for a rallying symbol, and the cultural memory of monarchy. What this means for resistance depends on Reza Pahlavi. Given the chance, could he emulate figures like Juan Carlos of Spain, who transitioned to democracy?

In summary, the call for the Shah's return is not just about politics. It delves into Iran's historical and cultural fabric, where kingship has long been intertwined with identity and hope.