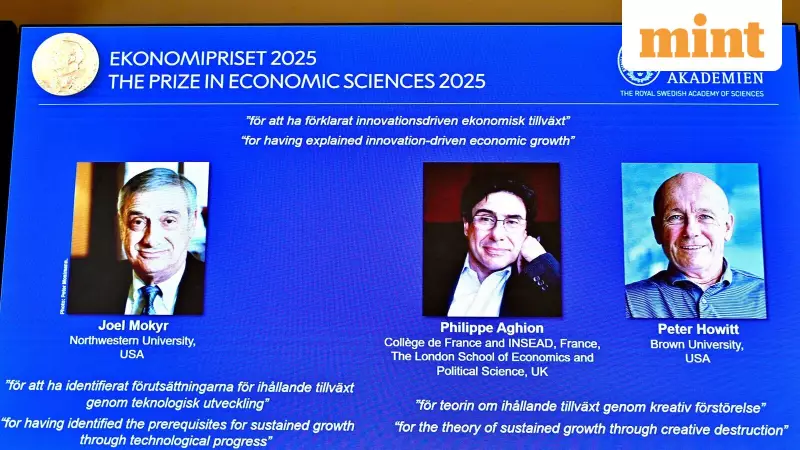

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics has delivered a powerful message for nations navigating the turbulent waters of technological progress. The prestigious award honours three scholars—Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt—for their work in decoding a central paradox: how did sustained economic growth begin and continue, despite the massive disruption it invariably causes? Their insights offer a crucial framework for India, a country standing at a critical juncture of digital transformation and economic ambition.

The Nobel Blueprint: Useful Knowledge and Creative Destruction

Laureate Joel Mokyr challenged the simplistic view that innovation alone fuels growth. He pointed out that major technological leaps, like the heavy plough and the printing press, occurred for centuries before the Industrial Revolution without triggering sustained rises in living standards. For instance, GDP per capita in England and Sweden showed minimal movement over four centuries prior.

Mokyr identified three essential prerequisites that finally ignited continuous growth. First, societies needed to develop "useful knowledge"—a fusion of prescriptive know-how (how to operate a technology) and propositional understanding (the science of why it works). Second, a cadre of skilled engineers and mechanics was required to turn abstract ideas into economic reality. Finally, and perhaps most critically, institutions had to foster an openness to change, allowing competing interests to negotiate rather than resist progress, as the Luddites famously did by destroying textile machinery.

The other laureates, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, provided the mathematical backbone with their model of "creative destruction." This framework illustrates how new innovations constantly make older ones obsolete, a process that sustains aggregate economic growth even as it causes turmoil at the level of individual firms and workers. Their work reveals a delicate balance: while monopolies can stifle new entrants, excessive competition can also kill the incentive to innovate. Governments, therefore, must walk a tightrope, supporting research and development while mitigating the "business stealing" effect of new technologies.

India's Strategic Trilemma: Frontier, Adaptation, and Buffers

For India, the Nobel lessons crystallise into three pressing challenges. The first is a strategic choice: with finite resources, should the nation strive to innovate at the global technological frontier, or focus on adapting and deploying existing technologies? The research suggests that frontier innovation is not a prerequisite for substantial growth. Using the analogy of a bicycle race, the rider in second place, sheltered from the wind, can still finish in impressive time. For India, widespread deployment of technology through efficient labour markets, skill development, and bankruptcy reforms may be less glamorous than building AI centres but is potentially more consequential for broad-based growth.

The second challenge is contextual adaptation. India is a labour-abundant country with a large and growing working-age population. Basic economics would suggest prioritising labour-intensive production. Yet, there is a paradox: India's export basket is shifting from textiles to more capital-intensive engineering goods. The application of technology must be tailored. Take Artificial Intelligence (AI): nearly half of India's working-age population is in agriculture, where AI can boost productivity. Initiatives like the PM-Kisan chatbot, which uses voice-enabled interfaces to facilitate direct benefit transfers, demonstrate how technology can be adapted for contexts with low digital literacy. The task is to scale such solutions cost-effectively.

Managing the Human Cost of Progress

The third and most urgent challenge is managing the labour market disruptions inherent in technological transitions. The Nobel work underscores that the benefits of creative destruction are not automatically shared equitably. India must strengthen both active and passive labour market policies. Active policies include training programmes, skill development, and employment subsidies. Passive policies encompass unemployment insurance and other social security benefits.

Globally, median spending on active labour market programmes is a meagre 0.3% of GDP. India's spending is primarily focused on active schemes like the rural job guarantee (MGNREGA). However, with over 90% of jobs in the informal sector, most workers have minimal safety nets between jobs or support for reskilling when moving across sectors. The new labour codes are a step toward reform, but the fundamental question remains: can India implement the complementary policies needed to ensure the gains from technology are distributed fairly?

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics serves as a sobering reminder. Two centuries of unprecedented growth, which saw GDP per capita in the US and UK increase twentyfold, is a brief chapter in human history. Progress cannot be taken for granted. For India, the path to sustained prosperity lies not just in chasing the next technological breakthrough, but in consciously nurturing the institutional frameworks that harness creative destruction while protecting those it displaces. The nation's success will hinge on its ability to remain open to change while innovatively managing the disruption that follows.