A groundbreaking new study has issued a stark warning: thousands of patients across northern India, including the National Capital Region, are suffering through preventable pain. This widespread suffering persists because palliative care remains deeply misunderstood, severely underused, and poorly integrated into the region's standard healthcare systems.

The Stark Reality of Unmet Need

For millions of Indians battling life-limiting conditions like cancer, organ failure, dementia, or chronic pain, palliative care provides essential relief. It helps patients breathe easier, sleep better, and maintain their dignity. However, the demand for this compassionate care catastrophically outweighs its availability. Nationally, an estimated 7 to 10 million people require palliative care each year, yet fewer than 4% actually receive it. In north India and the NCR, this gap is even more pronounced, with most patient referrals happening dangerously late in their illness.

Researchers identify a critical barrier: the pervasive misconception that palliative care is solely for a patient's final days. This misunderstanding delays access to support that could alleviate suffering much earlier. A recent meta-analysis quantifies India's need at approximately 6.2 people per 1,000 population, highlighting the immense scale of unaddressed demand.

AIIMS-Led Training Model Shows the Path Forward

The same study, however, provides rare and encouraging evidence that this crisis can be reversed swiftly. Led by AIIMS Delhi, a multi-centre research project evaluated a three-phase palliative care capacity-building programme conducted across north India from 2023 to 2025. The initiative aimed to strengthen the skills of healthcare providers and expand access in a region where about 12% of older adults need such care.

The programme spanned nine centres of excellence and 90 district hospitals, including facilities in Delhi, Jammu, Srinagar, Chandigarh, Ludhiana, and Udaipur. Doctors and nurses received structured training in crucial areas like pain relief, symptom management, and effective communication with patients and families.

The results were promising. Participating hospitals reported smoother clinical workflows, improved documentation, and more confident healthcare providers. This directly translated into faster relief for patients and fewer days spent enduring unmanaged pain. The project demonstrated successful collaboration across diverse institutions, including AIIMS Rishikesh, AIIMS Nagpur, NCI-Jhajjar, the Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, multiple medical colleges, and government hospitals in Jammu and Kashmir, along with specialists from Apollo Hospitals in Delhi.

Sustaining Gains and Scaling the Solution

The study also flagged important challenges. Follow-up assessments revealed that knowledge levels among trained staff tended to dip over time, indicating that skills fade without consistent reinforcement. Some hospitals also faced difficulties with systematic data recording, which limits insights into patient demographics and care delivery.

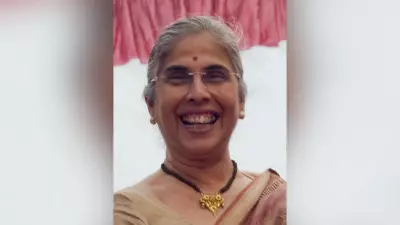

Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar, the project's principal investigator and former chief of IRCH and head of Palliative Medicine at AIIMS, emphasized that continued follow-up and on-ground support are essential. "In the next phase, we aim to integrate palliative care in a structured manner within emergency departments so that district-level doctors can manage pain and symptoms locally," she stated. Dr. Bhatnagar added that this approach "will reduce unnecessary referrals and allow patients to receive comfort and dignity at homes, close to their families, rather than spending their final days in ICUs."

Published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, the study concludes with a powerful dual message: targeted training can rapidly transform palliative care delivery, but only strong, systemic support can sustain those improvements. Researchers advocate for regular refresher courses, stronger digital documentation systems, and the formal inclusion of palliative care curricula in medical and nursing education across India. They assert that this model is not only scalable nationwide but also holds lessons for developed countries with uneven palliative care systems.