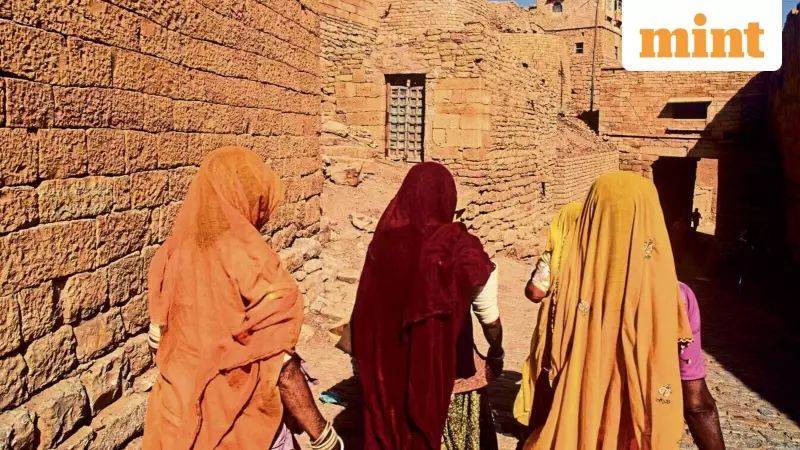

In April 1937, the junior Maharani of Alwar expressed a bold desire: to go for a joy ride in an aeroplane. For a Rajput royal woman of her stature, this was no simple outing. Bound by strict codes of purdah or seclusion, she could not be seen by men outside her immediate family circle, making the adventure a logistical challenge.

The Elaborate Precautions for an Aerial Purdah

The state machinery swung into action to ensure tradition was upheld, even in the skies. A senior official first personally inspected the six-seater aircraft to be "perfectly certain" it complied with purdah norms. Not leaving anything to chance, he later sent his wife to double-check the arrangements. Inside the plane, a physical barrier was erected to completely cut off the pilot from the passenger cabin. Furthermore, the windows were fitted with curtains, which remained drawn until the plane reached a safe altitude. To eliminate public gaze, only the Maharani's own retainers were permitted near the airstrip.

Despite these meticulous efforts, the flight backfired. British officials were aghast, viewing the Maharani's act as a severe violation of ladylike decorum. The technical adherence to purdah—airborne purdah—was seen as mocking the very spirit of the rule. This incident highlights the deep-rooted and complex role purdah played in India's social and political fabric.

A Contested History: Origins and Evolution of Purdah

The institution of purdah in India has a debated origin. While controlling women's mobility is ancient, the practice of systematic, everyday seclusion is widely linked to the era of Islamic rule. As Muslim elites from Persia and West Asia brought the custom to India, it became a marker of status and fashion in courtly circles. A common belief suggests Hindus adopted purdah to protect women from invaders, but historians offer a more nuanced view. Groups like the Rajputs, integrating into the new imperial order, began emulating Muslim courtly practices—much like adopting the flowing jama—with purdah being one such borrowed symbol of elite identity.

This is not to say seclusion was unknown before. In Kerala, Namboodiri Brahmin women lived in seclusion, using large parasols to shield themselves when visiting temples—not from Muslims, but from Hindus of other castes. Ideas of modesty also varied wildly. In north India, covering one's head was a sign of respect, while in Kerala, women entered sacred spaces topless as per protocol. Clearly, purdah was often less about modesty and more about signifying status and social distinction.

Purdah in Practice: Exceptions, Politics, and Decline

The application of purdah was never uniform. Among the Marathas in the early 19th century, practices differed: women at the Scindia court observed some purdah, while those in Nagpur appeared unveiled in public. In the 1860s, the ruler of Bhopal, Sikander Begum, famously defied norms by dressing like a man, sharing a hookah with a male French visitor, and overseeing male dance performances.

In the patriarchal north, purdah was tightly linked to family honour. A chilling 17th-century tale recounts Rajput king Dalpat Rao of Datiya preparing to kill his wife during a river crossing rather than let her be seen unveiled. The colonial state had a conflicted relationship with the custom. While they enforced it, as with the Alwar Maharani, they also found it a political hindrance. Veiled women influencing rulers behind screens, like in 19th-century Delhi or Jaipur, made it harder for British "advice" to prevail. Officials in Gwalior once found themselves "arguing with a bamboo curtain" wielded by a shrewd queen mother.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, purdah faced growing criticism from modern, educated Indians who saw it as backward. Reformers like Mahatma Gandhi invoked mythological figures like Draupadi and Sita to argue against it. Yet, resistance remained fierce, as many men saw the custom as integral to their community's identity. Ultimately, the story of purdah is as much about male prestige and power as it is about women's seclusion, a tradition that adapted, was weaponized, and was contested across centuries of Indian history.