Bengaluru in the 1870s: A View from the Top

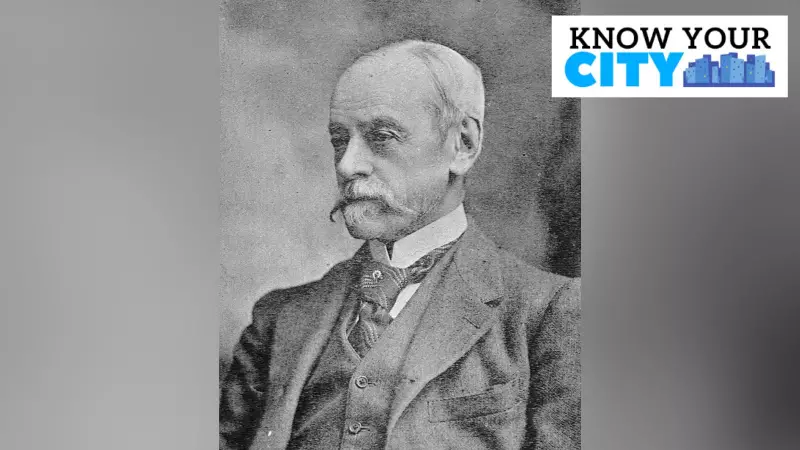

Sir Lewin Bentham Bowring once ruled Bengaluru, and his eyes captured the city in a pivotal era. The 1860s and 70s shaped Old Bengaluru into the modern hub we know today. After the chaos following the war with Tipu Sultan, Sir Mark Cubbon stepped in as the third commissioner of Mysore in 1834 to restore order. Bowring took over later, building on this stable foundation with new infrastructure and education projects. He even left his name on the future Bowring Institute.

Population and Growth in 1869

Bowring's memoirs, Eastern Experiences, written in 1871, offer a rich source of information. They provide an upper-class British perspective on Bengaluru during his time. According to his records, Bengaluru had a population of 1,32,000 in 1869. This included 79,000 people living in the newly built cantonment area. Only 3,900 were Europeans and Englishmen, with soldiers among them. Another 2,500 were 'Eurasians,' likely referring to the Anglo-Indian community.

The city's growth started when British forces moved from Srirangapatnam. That location had proven unhealthy, with soldiers often falling ill from fever. Traders and merchants followed the military, along with the civil administration of the British Raj. Trade picked up again in 1864 with the arrival of railway links, boosting movement and commerce.

Climate and Health in Old Bengaluru

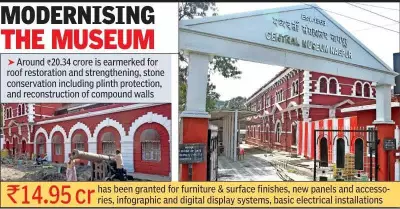

Bowring praised Bengaluru for its pleasant climate and good health. He noted an absence of diseases at the time. The temperate weather allowed soldiers to play cricket on the parade ground for eight months each year. Like many British accounts, he highlighted the city's ability to grow fruits and vegetables valued by Europeans. He also mentioned the Government Museum and Lalbagh multiple times. Bowring wrote, "The garden is a beautiful retreat, and is frequented by all classes, the natives being attracted to it mainly by the menagerie attached to it."

Governance and Trade Challenges

Bowring foresaw complications from the split sovereignty in Bengaluru. The cantonment was under British control, while the walled pete remained under the Maharaja's rule. This issue never resolved before Independence. He proposed a solution: the British take full control of the area around Bengaluru. In exchange, Srirangapatnam could go to the princely state. Although Srirangapatnam's revenues were lower, Bowring believed its historical significance balanced the deal. This exchange never happened.

Regarding trade in the walled town, Bowring was not impressed. He stated, "...nor is Bangalore remarkable for any manufactures, except carpets of rare quality, rugs, and articles of mixed silk and cotton." However, he acknowledged that some merchants, called Shettis, were wealthy. They enjoyed privileges like wearing gold signet-rings and immunity from certain taxes.

Royal Tributes and Legacy

Katharine Bowring, in letters included in the memoirs, recorded the death of Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar III. She described the tribute paid to his heir on the parade ground. Two thousand soldiers assembled there the day after the cremation. Twenty-one cannons fired to salute Chamarajendra Wadiyar, the tenth of that name. This ground later became part of today's MG Road, known then as South Parade. The Wodeyars did not regain full rule until 1881, but respect for the king's station remained strong.

Bowring's writings offer a vivid snapshot of Bengaluru's transformation. They highlight population shifts, climate benefits, and governance struggles that defined the 1870s.