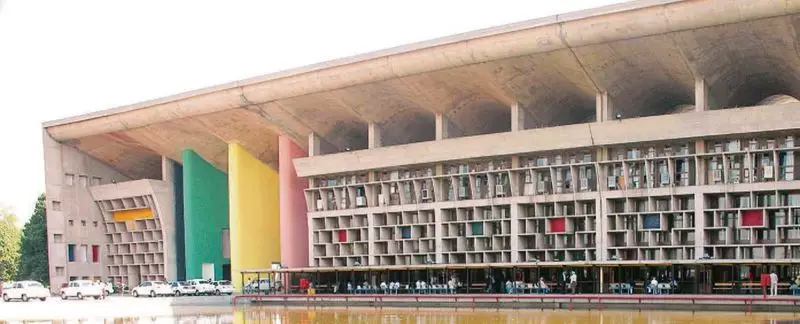

The Punjab and Haryana High Court has delivered a significant ruling, clarifying the broad powers of trial courts to summon individuals as accused. The court stated that a court can summon any person to face trial the moment evidence collected during an investigation points a finger at them, even if they were not originally named in the First Information Report (FIR).

Court's Authority to Summon Based on Evidence

This important clarification came from Justice Vikas Bahl as the High Court dismissed a petition filed by a man named Pardeep. Pardeep had sought to quash an order from a sessions court in Yamunanagar, Haryana, which had summoned him as an additional accused in a criminal case. The sessions court's decision was based on evidence that emerged after the filing of the initial FIR.

The case originates from an incident on March 12, 2021, in Yamunanagar. An FIR was registered under several sections of the Indian Penal Code, including 323 (voluntarily causing hurt), 341 (wrongful restraint), 506 (criminal intimidation), and 34 (acts done by several persons in furtherance of common intention). The complaint alleged that the petitioner, Pardeep, along with others, had assaulted the complainant.

Investigation Reveals New Details

During the police investigation, however, Pardeep was not initially found to be involved. The investigating officer filed a closure report concerning Pardeep, which the magistrate accepted in January 2022. The trial proceeded against the other named accused.

A crucial turn of events occurred when one of the co-accused, facing trial, filed an application. This application claimed that Pardeep was, in fact, present at the scene and was equally involved in the alleged crime. The trial court, after examining this new claim and the existing evidence, decided to summon Pardeep as an additional accused in July 2023.

Pardeep challenged this summoning order in the High Court, arguing that since he had been cleared by the police and the magistrate had accepted the closure report, the trial court had no authority to summon him later.

High Court's Legal Reasoning and Dismissal

Justice Vikas Bahl, in the ruling, firmly rejected this argument. The High Court emphasized that the power of a sessions court to summon a new accused is derived directly from Section 319 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). This section grants the court wide discretion if it appears from the evidence that any person not already on trial has committed an offence.

The court meticulously explained the legal position. It stated that the acceptance of a police report (like a closure report) by a magistrate does not permanently bar or estop the court from exercising its power under Section 319 CrPC at a later stage. The key factor is the evidence that surfaces during the trial. If such evidence indicates the involvement of a new person, the court is fully empowered to summon them, regardless of earlier investigative conclusions.

"The trial court has every power to summon any person as an accused, if on the basis of evidence which comes before it, the court is of the opinion that such a person has committed an offence," the High Court observed. It further added that the moment evidence points a finger toward an individual, the court is entitled to call them in to face the trial.

After reviewing the facts, Justice Bahl found no error in the Yamunanagar sessions court's order. The High Court concluded that the trial judge had correctly applied the law based on the material presented. Consequently, the petition was dismissed, upholding the summoning order against Pardeep.

Implications of the Ruling

This ruling reinforces the proactive role of the judiciary in ensuring that all individuals against whom credible evidence exists are brought to trial. It underscores that the court's power is independent of the police's initial findings or the magistrate's acceptance of a closure report. The judgment serves as a crucial reminder that the pursuit of justice is dynamic, and courts retain the authority to correct course when new evidence emerges during the judicial process itself.

The decision strengthens the legal framework allowing courts to prevent individuals from evading trial simply because they were not named in the original FIR or were initially cleared by the investigating agency. It affirms the principle that the truth-seeking function of a trial is paramount.