The Pattern Seeker: How Marcus du Sautoy Reveals Mathematics in Everything

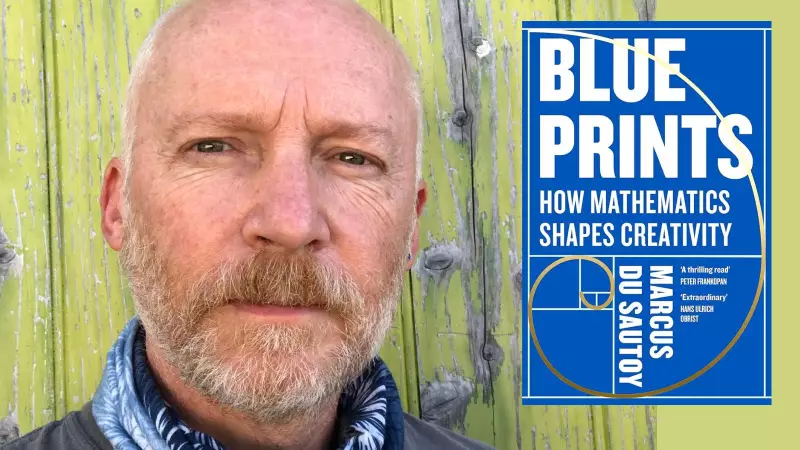

At the bustling Jaipur Literature Festival, amidst the vibrant discussions of poetry and politics, an unexpected figure captivated audiences: Marcus du Sautoy, the Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Far from the stereotypical image of a mathematician lost in equations, du Sautoy spoke eloquently in stories, weaving a narrative that positions mathematics not as a cold, numerical discipline but as the hidden architecture of creativity, beauty, and human perception. In a quiet corner away from the main stages, he shared insights from his forthcoming book, Blueprints, arguing that mathematics is the quiet engine driving our world.

Mathematics as the Language of Creativity

Du Sautoy began by delving into the works of Shakespeare, highlighting how the Bard intuitively employed mathematical principles. "When Shakespeare has the Three Witches cast Macbeth’s lot, he uses the number seven, and in Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, he reaches for eleven," du Sautoy explained with a conspiratorial warmth. For him, these are not mere curiosities but clues to a deep, intuitive collaboration between art and mathematics. He emphasized that creativity is inseparable from mathematics, with the relationship flowing both ways. This conviction guides his work as he moves between lecturing on zeta functions at Oxford and discussing choreography with dancers in Birmingham, always seeking to reveal the connecting patterns.

AI as an Alternative Intelligence

When the conversation shifted to Artificial Intelligence, often framed as a threat, du Sautoy offered a nuanced correction. "I wouldn’t call it artificial intelligence; I think it’s an alternative intelligence," he stated. He views AI not as a rival to human creativity but as a lens that illuminates aspects we might overlook. For instance, he described an MIT experiment where AI detected false smiles more accurately than humans, seeing this as a form of translation that could aid autistic individuals with social cues through augmented-reality glasses. However, he noted a crucial boundary: "The really important difference is embodiment. AI is very unembodied, learning from digital data, while much of our intelligence stems from physical engagement."

Simplifying Mathematics for the Layman

As a translator of complex mathematical concepts, du Sautoy shared his approach to making mathematics accessible. "Understanding what not to say is more important than understanding what you should say," he advised, stressing the importance of storytelling over technical details. His method involves "finding the door" by starting with what people already love, such as music, cricket, or classical dance. By revealing the mathematics inherent in these passions, he breaks down barriers and fears, showing that nature itself is full of mathematical patterns.

The Creativity of Mathematical Discovery

Addressing the philosophical question of whether mathematics is invented or discovered, du Sautoy leaned toward discovery but with a creative twist. He likened mathematicians to curators of truths that exist independently of humans, citing Jorge Luis Borges’s "The Library of Babel" to illustrate that creativity lies in the choices we make. "The creativity is in the composer making a choice," he said, defining a mathematical breakthrough as something new, surprising, and valuable, with surprise being inherently emotional.

The Allure of Unsolved Problems

No discussion with du Sautoy would be complete without touching on great unsolved problems like the Riemann Hypothesis. He finds beauty in their stubbornness, arguing that ease would render mathematics boring. "Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic, and the Riemann Hypothesis is about proving there is no pattern at their heart," he explained, emphasizing the excitement of the journey toward proof. He referenced the film Good Will Hunting to highlight how challenge adds magic to mathematical pursuits.

Symmetry and Evolutionary Mathematics

Du Sautoy traced our preference for symmetry back to evolutionary mathematics, explaining that symmetrical faces and flowers signal health and vitality. "Why are we drawn to a face with symmetry? Because symmetry is very hard to make, indicating good genetic heritage," he said. This, he argued, is not a cultural accident but a mathematical truth embedded in nature, with mathematics serving as the language that reveals significant patterns.

Mathematics in Football and Beyond

Extending his insights to sports, du Sautoy highlighted the richness of mathematical thinking in football. He shared an anecdote about his East London football team, which improved its performance after switching to prime number shirts. "There is a lot of mathematics in football, from pattern recognition to probability," he noted, laughing. Even when players are unaware, the game involves collective calculation and strategic patterns.

Mathematics as the Foundation of Reality

In a metaphysical turn, du Sautoy inverted the saying "If there is a God, He must be a mathematician" to propose that mathematics itself is the foundational structure of existence. "Mathematics doesn’t need a moment of creation; it is the set of all possible structures," he asserted. This perspective liberates mathematics from physical confines, aligning it more closely with literature than physics due to its ability to create logically consistent, abstract worlds.

We Are All Mathematicians at Heart

Concluding on a generous note, du Sautoy challenged the notion that mathematics is only for experts. "Although many people say, 'Oh, I’m not a mathematician,' I think actually we’re all mathematicians at heart," he said. He explained that the human brain has evolved to navigate chaos through pattern searching, the essence of mathematics, making it an innate part of our perception and interaction with the world.