For over a hundred years, tuberculosis has stubbornly clung to humanity, defying medical advances and public health efforts. Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, this ancient disease continues to claim lives at an alarming rate. In 2023, global estimates pointed to 10.8 million new cases and 1.25 million deaths. India bears the heaviest burden, reporting over 2.6 million cases in 2024. The central, uncomfortable question remains: why does TB persist so effectively?

The Stealthy Strategy of Dormant TB

A significant part of the answer lies in the bacterium's ability to become dormant. After infection, TB bacteria can enter a latent, sleep-like state. In this dormant phase, they cause no symptoms and are not contagious, silently residing in the body. The danger emerges when a weakened immune system—due to other illnesses, HIV, or medications—allows these dormant cells to reactivate into full-blown, infectious TB.

This dormancy is also where conventional antibiotics fail. Most drugs target actively growing bacteria. Dormant cells, in their near-static state, develop a tolerance, surviving standard treatment courses and leading to relapse. This is a distinct phenomenon from genetic antibiotic resistance.

IIT Bombay-Led Team Cracks the Membrane Code

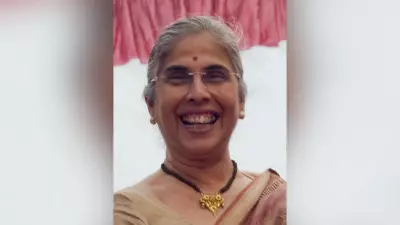

A collaborative research team led by Prof. Shobhna Kapoor from IIT Bombay's Department of Chemistry and Prof. Marie-Isabel Aguilar from Monash University set out to solve this mystery. Their groundbreaking findings, published in the journal Chemical Science, pinpoint the bacterial cell membrane as the key defender.

Since working with live TB is hazardous, the team used its safer relative, Mycobacterium smegmatis, mimicking active and dormant states. They then tested four common TB antibiotics: rifabutin, moxifloxacin, amikacin, and clarithromycin. The results were clear: dormant bacteria required two to ten times higher drug concentrations to be affected.

"The same drug that worked well in the early stage would now be needed at a much higher concentration to kill the dormant cells," explained Prof. Kapoor. Crucially, this was not due to genetic mutations.

A Molecular Census Reveals a "Thick-Skinned" Defence

The researchers performed a detailed lipid analysis of the bacterial membranes using advanced mass spectrometry. They catalogued over 270 lipids. The difference was stark: active cells had membranes rich in glycerophospholipids and glycolipids, making them fluid. Dormant cells, however, were armored with dense, wax-like fatty acyls, creating a rigid barrier.

Anjana Menon, the PhD scholar from IITB-Monash Research Academy who is the lead author, noted, "We found clear differences between the lipid profiles of active and dormant cells." A critical lipid called cardiolipin, which maintains membrane flexibility, plummeted in dormant cells. "When its level falls, the membrane becomes tighter and less permeable," Menon added.

Tracking the antibiotic rifabutin confirmed the theory: it easily entered active cells but was blocked at the rigid outer wall of dormant ones. "The rigid outer layer becomes the main barrier. It is the bacterium's first and strongest line of defence," stated Prof. Kapoor.

A New Strategy: Loosen the Armour, Boost Old Drugs

The study proposes a promising therapeutic shift. Instead of developing entirely new drugs, the researchers suggest combining existing antibiotics with molecules that can loosen the membrane's rigid structure. Their candidate: antimicrobial peptides.

These small proteins can gently pry open bacterial membranes. "These peptides alone don't kill the bacteria, but when combined with antibiotics, they help the drugs enter and act more effectively," Prof. Kapoor elaborated. This approach could potentiate current treatments, making them effective against the persistent dormant population.

The next crucial step is to validate these findings with the actual TB strain in high-security biosafety labs. Ms. Menon expressed confidence, stating, "Our lipid analysis is very detailed. It can easily be applied in labs that work with the actual TB strain."

If successful, this breakthrough could lead to shorter, more effective treatment regimens, offering a new weapon against a disease that has outsmarted medicine for generations.