Egyptian Archaeologists Reunite Colossal Ramesses II Statue After Century Apart

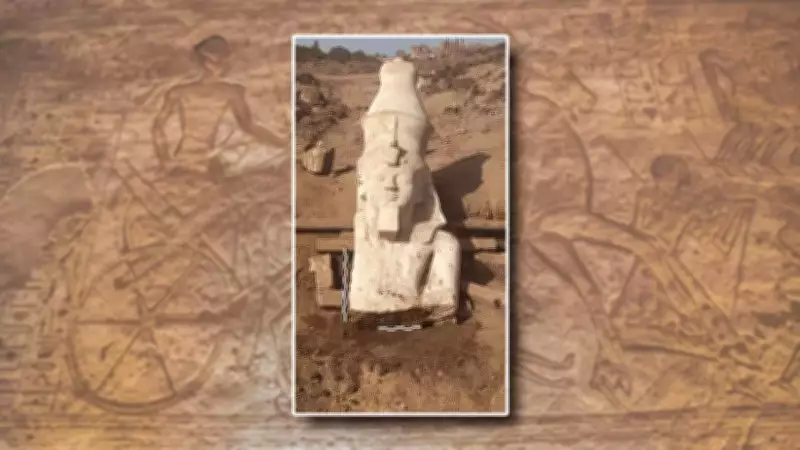

Hidden beneath Egypt's shifting sands for nearly a hundred years, a missing piece of ancient history has dramatically reemerged. Archaeologists conducting excavations in central Egypt have successfully uncovered the upper section of a colossal seated statue depicting Ramesses II, one of the nation's most iconic and powerful pharaohs. This monumental fragment has been connected to a lower portion that was originally discovered back in the 1930s, sparking renewed enthusiasm and scholarly interest in restoring the complete sculpture as a single, unified monument.

El Ashmunein Discovery at Hermopolis Magna

The statue fragment was unearthed at the archaeological site of El Ashmunein, which sits directly atop the ruins of the ancient city known as Hermopolis Magna. This historic location once functioned as a major religious center dedicated to Thoth, the ibis-headed deity associated with writing, wisdom, and knowledge. The archaeological layers at this site reveal evidence of continuous human occupation across multiple historical periods, which frequently complicates and challenges excavation efforts.

The newly discovered piece stands approximately 12.5 feet tall and portrays the pharaoh seated in a formal, ceremonial pose. Carved meticulously from limestone, the statue fragment displays a detailed ceremonial headdress and a partially preserved uraeus cobra, which served as a powerful royal symbol closely linked to divine kingship and pharaonic authority. Experts analyzing the craftsmanship suggest this monument was intentionally designed to project royal power and influence far beyond Egypt's traditional capital regions.

Connecting to the 1930 Discovery

Researchers quickly established a connection between this newly uncovered fragment and a lower statue half that was discovered in 1930 by the renowned German archaeologist Günther Roeder. At that time, Roeder carefully documented the statue's base but found no trace of the upper portion. For many decades, the statue remained frustratingly incomplete, representing an archaeological puzzle missing its most expressive and defining element.

The recent excavation was jointly led by Basem Gehad from Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and Yvona Trnka-Amrhein from the University of Colorado Boulder. Their archaeological team reportedly uncovered the fragment lying face down in moist soil while investigating another sector connected to earlier papyrus discoveries. Detailed measurements and thorough stylistic analysis strongly indicate that both statue parts belong together, forming a single, coherent sculpture.

Ancient Pigments Reveal Lost Vibrancy

One particularly surprising detail that has captured significant scholarly attention is the presence of ancient pigment traces. Researchers have identified both blue and yellow coloring embedded within the limestone surface, suggesting that various parts of the statue once displayed vivid and elaborate decoration. Most Egyptian sculptures have lost their original paint over millennia due to environmental erosion and prolonged exposure.

The fragment's preservation appears especially remarkable given the environmental challenges present in the region. Changes in groundwater levels following the construction of the Aswan Low Dam have affected archaeological layers at the site, raising legitimate concerns about mineral leaching and stone fatigue that could compromise preservation efforts.

Statue Reconstruction Proposal

Egyptian authorities have reportedly submitted a formal proposal to the Supreme Council of Antiquities seeking official approval to reassemble the complete statue. If restoration efforts proceed as planned, the monument could potentially become one of the tallest seated representations of the pharaoh located outside major temple centers such as Abu Simbel, Luxor, and Karnak.

Officials have not yet confirmed whether the restored statue would remain permanently at its original discovery site or be relocated to a museum setting for enhanced preservation and public display.

Why Ramesses II Still Dominates Egyptian Archaeology

Ramesses II ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1213 BCE and remains widely celebrated for his extensive large-scale construction projects, ambitious military campaigns, and prolific temple building along the Nile Valley. Statues placed strategically in regional religious centers reinforced royal presence and divine legitimacy far from administrative capitals, serving as powerful symbols of pharaonic authority.

Excavations at El Ashmunein are expected to continue through 2026, with archaeological teams expanding into nearby sectors using advanced subsurface mapping techniques and detailed stratigraphic analysis. Archaeologists strongly suspect that additional fragments from the same statue group might still be buried at the site, waiting to be discovered.