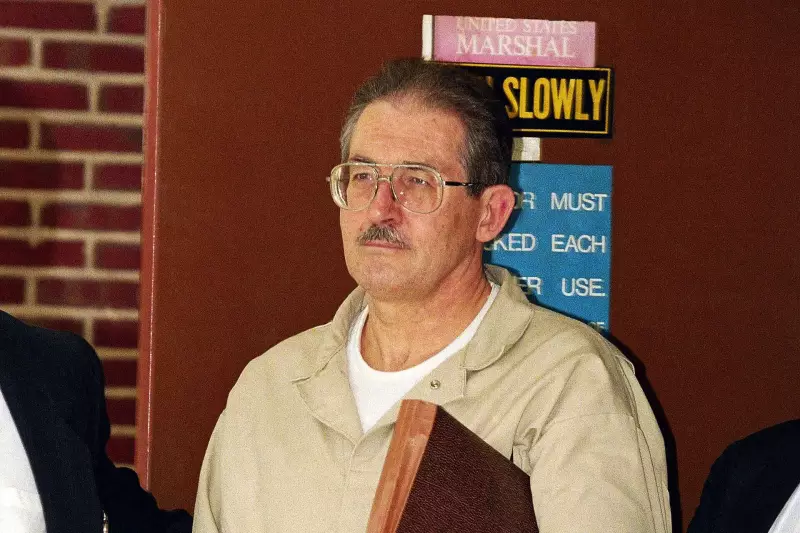

The death of Aldrich Ames at 84 did not elicit softened obituaries from America's major newspapers. The New York Times branded him a "C.I.A. Turncoat Who Helped the Soviets," while The Washington Post delivered a harsher verdict, calling him "the most damaging CIA traitor in agency history." This unanimous condemnation underscores a profound truth: Ames is not remembered for being fascinating, but for being devastatingly ordinary. His story is one of mediocrity, resentment, and transactional betrayal that left a permanent scar on American intelligence.

The Alcoholic Traitor: A Mediocre Man in a Sensitive Seat

To understand Aldrich Ames, one must discard the glamorous myths of espionage. He was not a brilliant ideologue. He was a second-generation CIA man who inherited espionage as a family trade, not a calling. His father, also an agency man, struggled with alcoholism—a shadow that would loom over the son's life. Ames joined the CIA and was repeatedly flagged as a mediocre field officer, better suited to a desk. He was a heavy drinker with a resentful attitude, believing the agency owed him more.

Despite his flaws, institutional inertia propelled him upward. By the early 1980s, through a system that mistook longevity for reliability, Ames held the extraordinarily sensitive position of counter-intelligence chief for the Soviet division. This role gave him access to the crown jewels of American espionage: the identities of Soviet officials secretly working for the West. His rise was not due to merit but to a complacent system promoting its own.

The Transactional Betrayal: From Debt to Disaster

Ames did not defect for ideology. He unraveled. By the mid-1980s, his alcoholism was a crutch, his personal life collapsing under debt and divorce. Bitter and financially desperate, he took a shockingly simple step. In 1985, he walked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington, offered his services, and handed over names for money. There was no sophisticated courtship—just a brazen, panic-driven sale.

What followed was a catastrophic chain reaction. Fearing exposure from the very assets he was meant to protect, Ames chose annihilation. He betrayed them all, giving Moscow a comprehensive map of Western intelligence networks within the Soviet system. Alcohol enabled this, dulling caution and allowing him to frame treason as a mere transaction. The KGB paid him millions, and Ames embraced a lavish lifestyle that finally made him feel valued.

The Devastating Aftermath and Banal Evil

The damage was immediate and profound. As Ames's intelligence flowed to Moscow, Soviet counter-intelligence moved swiftly. Western agents began disappearing; at least ten were executed. Networks built over decades evaporated overnight. The CIA lost its most vital human intelligence channels at the Cold War's critical juncture.

Beyond the tragic human cost, Ames inflicted long-term strategic blindness. The CIA's understanding of Soviet capabilities became distorted, polluted by disinformation. Yet, when confronted, Ames remained detached, dismissively claiming espionage was overrated and the deaths were expendable in a meaningless game. His betrayal was animated not by conviction but by contempt.

The most damning aspect of the Ames case is how long the obvious was ignored. By the late 1980s, his lifestyle—a cash-bought house, a Jaguar, tailored suits—blatantly contradicted his salary. Colleagues noticed, but the CIA's internal security, hampered by bureaucracy and a reluctance to suspect one of its own, moved with lethal lethargy. The investigation stalled at one point when the sole officer assigned went for training.

Only when the FBI took over did the truth emerge. Surveillance and financial records built an irrefutable case. Aldrich Ames was arrested in February 1994, ending nearly a decade of betrayal. He pleaded guilty, accepted a life sentence, and to the end, downplayed his actions' significance—a final deflection from a man who believed nothing mattered beyond his own survival. His legacy is a stark reminder of how ordinary weakness, left unchecked in a system of trust, can cause extraordinary ruin.